Tripwires

Or, how to avoid Nazi takeovers and other threats with reverse reasoning

Hello again! I’m back from my new baby hiatus and eager to get back to semi-monthly cadence!

When I was a kid, I remember a friend’s dad digging in his pocket for something and pulling his passport out as he searched. I asked why he was carrying his passport. He said it’s because he’s a Jew, and history has taught Jews in gentile lands to be ready to flee at a moment’s notice.

In the Oscar-winning film The Pianist, the audience watches in anguish as a Jewish family in Poland rationalizes and underestimates the danger of the Nazi invasion.

It’s a historically-rooted illustration of optimism bias, where people underestimate the probability of bad things happening to them.

I believe optimism bias is extreme and ubiquitous when the threat is a “tipping point”-type of cascading threat. War certainly counts. So does cancer. So do pandemics; people underestimated the risk of Covid because it spread exponentially. When you are at 1 or 2 cases, it’s hard to imagine 1000 cases, and when you are at 10,000 cases, it’s hard to imagine millions. Similarly, it’s easy to underestimate the cascading catastrophes that climate change will bring.

Risks and the Flow of Reasoning

The problem is that it is harder to reason forward than to reason backward.

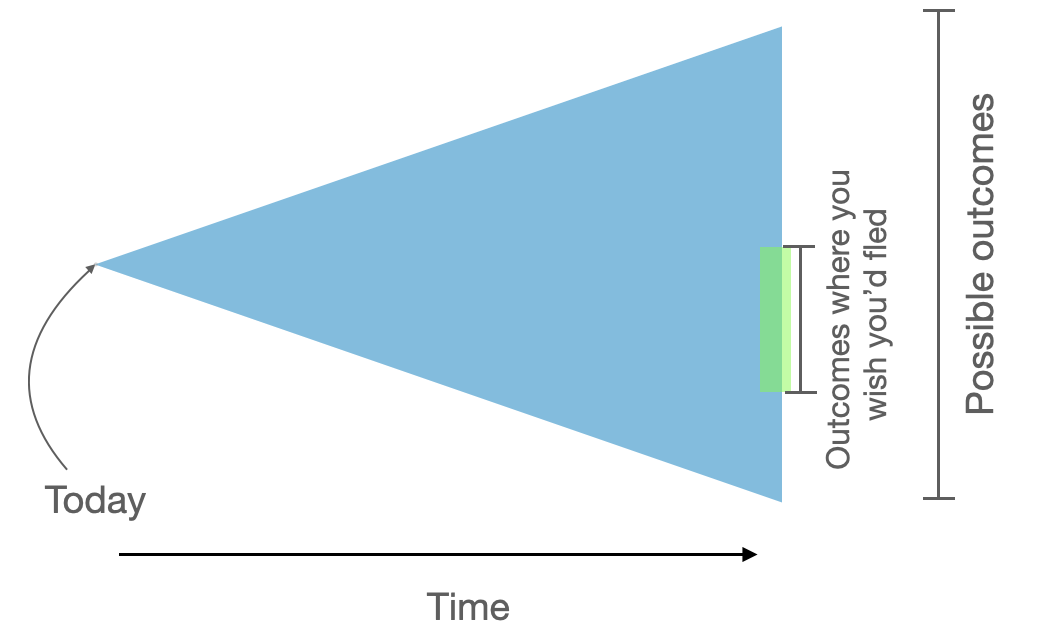

To illustrate, gven what you know of the world today, mentally forward-simulate all the outcomes the world could take a year from now.

Now, what’s the probability you’ll need to grab your passport and flee before a year has passed? To answer, count all the outcomes where you would have wished you’d grabbed your passport and fled and divide by the total number of outcomes you imagined.

Not so easy, is it? I sure can’t do it. The possible outcomes are too vast. And I’d guess that I’m heavily biased towards imagining certain outcomes and discounting others.

Now try reasoning backward instead of forward. Under what circumstances would things have become so dire that you wished you’d grabbed your passport and fled? Enumerate as many as you can, focusing on what is plausible, not just what is likely.

Now step backward in time from those outcomes, imagining what things would have to happen for those outcomes to occur. Then imagine what things would have to precede those things, etc., iterating back to the present.

That reasoning process is much easier. In probabilistic terms, for a given cause and effect, usually, P(cause|effect) is much higher than P(effect|cause). So given the cause, it is hard to reason forward to the effect if P(effect|cause) is low. But given the effect, it is easier to retrospectively attribute the cause if P(cause|effect) is high.

Tripwires

One of my guilty pleasures is Lee Child’s “Jack Reacher” series. In one of the books called “Tripwire,” the villain is a financial criminal who does nasty things to any unfortunate soul who threatens his operation.

The villain has long evaded detection through an early-warning system consisting of “tripwires” that trigger automated warnings when some investigator is sniffing around his assets or people, places, and objects associated with his criminal doings. His response to the warnings would be to tie up loose ends, cash in, transfer his assets, grab his passport, and flee the country.

Tripwires are an excellent way to use reverse reasoning to avoid optimism bias. As you reason backward in time from a bad outcome to the events that would have to occur before a bad outcome, you can create tripwires for that outcome.

For example, reasoning backward from out-of-control violent political riots after a contested 2024 US Presidential election, you could place a tripwire around the event that the national guard is called in, or that there are calls to arms by partisan cable TV hosts, or the government “temporarily” suspends habeas corpus. Going back further, you might track pundits who don’t believe there will be a problem to see if they suddenly change their mind or if powerful people or corporations are beginning to take their own precautions.

The tripwires trigger you to take a precaution. The closer in time the tripwire is to the ultimate bad outcome, the more severe the precaution, culminating in you grabbing your passport and fleeing. You pledge to yourself that when the tripwire is tripped, you exercise the precaution, regardless of how tempting it is to say, “This is fine.”

The challenge is not letting your optimism bias in the moment overcome your pledge to honor your tripwire. This error is, of course, what the villain in Tripwire did; he thought he’d hold out a few more days to close out a big deal. That’s how Reacher got him in the end.